The pandemic has once again placed the home at the centre of our lives. No longer a simple refuge at the end of a frantic day in the outside world, but occupied 24 hours a day; no longer a space dedicated only to domestic functions, but a multiuse station for the multiple activities of its inhabitants, it is now an object of critical considerations. Setting out from these premises, “Living the domestic landscape” proposes a reflection on the broader meaning of the home today and in the near future, with a particular focus not only on its organisational structure and consequent values, but above all for its spatial characteristics in relation to the emotional sphere and different lifestyles of its inhabitants. For this reason we considered it useful and stimulating to look back into the recent past, at the golden period of research into domestic space that produced so many important experiments in Italy. Perhaps precisely for the uniqueness of its results this contribution was set aside and replaced by other more urgent questions linked to urban development, infrastructures, and public services and spaces. To understand where we are today and pick up the thread of this interrupted discourse, the selection of projects presented in this issue, followed by an essay exploring potential research into contemporary domestic space, is dedicated to 10 domestic projects designed by leading architects between 1936 and 1978. Each offers diverse responses to questions linked to the renewal of domestic space raised by coeval society; each is a model for its non-replicability and uniqueness and each in our opinion is a bearer of spatial values and themes of research, still of value today, despite particular geographic circumstances and the passing of time. The first characteristic common to each of these examples is the close relationship between client and designer, two fundamental and in some cases coincident figures; a second is the proposal of innovative solutions that explore non-conventional residential conditions, in both the organisation of internal spaces and relations with urban environments and landscapes. All ten homes – 7 single-family, four of which are vacation homes, and three flats in urban buildings- share a fundamental peculiarity: they experiment with new forms of language identify interior spaces tailormade to their inhabitants and clients and establish a strong bond between creator and inhabitant, often fulfilling the dream of the “ideal home”. The aspects of originality and of interest, the salient characteristics of design and space of each of these 10 homes were commented by diverse authors who present multiple experiences and open questions related to the theme of domestic space, with the objective of asking broader questions about the quality and form of dwelling.

The pandemic has once again placed the home at the centre of our lives. No longer a simple refuge at the end of a frantic day in the outside world, but occupied 24 hours a day; no longer a space dedicated only to domestic functions, but a multiuse station for the multiple activities of its inhabitants, it is now an object of critical considerations. Setting out from these premises, “Living the domestic landscape” proposes a reflection on the broader meaning of the home today and in the near future, with a particular focus not only on its organisational structure and consequent values, but above all for its spatial characteristics in relation to the emotional sphere and different lifestyles of its inhabitants. For this reason we considered it useful and stimulating to look back into the recent past, at the golden period of research into domestic space that produced so many important experiments in Italy. Perhaps precisely for the uniqueness of its results this contribution was set aside and replaced by other more urgent questions linked to urban development, infrastructures, and public services and spaces. To understand where we are today and pick up the thread of this interrupted discourse, the selection of projects presented in this issue, followed by an essay exploring potential research into contemporary domestic space, is dedicated to 10 domestic projects designed by leading architects between 1936 and 1978. Each offers diverse responses to questions linked to the renewal of domestic space raised by coeval society; each is a model for its non-replicability and uniqueness and each in our opinion is a bearer of spatial values and themes of research, still of value today, despite particular geographic circumstances and the passing of time. The first characteristic common to each of these examples is the close relationship between client and designer, two fundamental and in some cases coincident figures; a second is the proposal of innovative solutions that explore non-conventional residential conditions, in both the organisation of internal spaces and relations with urban environments and landscapes. All ten homes – 7 single-family, four of which are vacation homes, and three flats in urban buildings- share a fundamental peculiarity: they experiment with new forms of language identify interior spaces tailormade to their inhabitants and clients and establish a strong bond between creator and inhabitant, often fulfilling the dream of the “ideal home”. The aspects of originality and of interest, the salient characteristics of design and space of each of these 10 homes were commented by diverse authors who present multiple experiences and open questions related to the theme of domestic space, with the objective of asking broader questions about the quality and form of dwelling.

LIVING THE DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE – Pg. 2

Editorial by Domizia Mandolesi

The “Classical Substrate” Creates Very Modern Masterpieces

The “Classical Substrate” Creates Very Modern Masterpieces

by Antonino Saggio

Villa Bianca occupied a large lot, measuring roughly 100 metres in length along the street by 63 metres in depth, in a suburban development at Corso Garibaldi 87 in the town of Seveso. The northern part of the site was subdivided and sold; the house now sits on an almost square lot measuring roughly 60 x 63 metres, passing from an original form open at the corner toward Via Sprelunga to an intercluded lot and transforming the perception, the proportions and the spatiality of the home. The completely asymmetrical position, very close to the main road, biased toward the south-east corner, was a result of the sum of characteristics, including the visibility of the house as much from the street as the views it offered. The structure of load bearing walls in reinforced concrete gives the construction the substance of a solid volume that would have been vitiated by infilling a framed construction. The villa was raised approximately 1.2 metres above the ground. On the one hand this choice elevated views out and on the other consented the insertion of windows to ventilate the half basement level, occupied by the laundry, garage and staff lodgings. Access to the house, at the raised ground floor, is provided by a stair/ramp at the back. There is a canonical arrangement with a serving zone and served zones at the sides. The serving zone, at the centre, features, aside from the entrance, the stair to the basement and first floor. On the north-east side is the large living room with a study that pushes outward and, in the south-east area, the kitchen, a service room and the dining area. At the first floor the stair provides access on the left toward the south-east to two bedrooms and toward the right to a large master bedroom with a study or annexed bedroom. Both benefit from access to a terrace/patio. From here a new stair leads to the solarium, topped by the famous canopies that play not only with the famous dynamic effect, but also offer protection against the sun and wind.

The Mediterranean as a Genius Loci

The Mediterranean as a Genius Loci

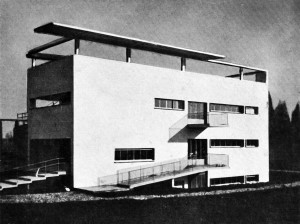

by Enrico Sicignano

In 1936 the builder Vincenzo Savarese chose Luigi Cosenza to design an important and delicate project for his home in the recently created and elegant SPEME district in Via Scipione Capece on the Naples Posillipo hillside. At the time Villa Savarese was a single-family home of four-storeys connected by a helicoidal stair providing access to a solarium and with a glass block tower. The two residential levels above ground (day and night functions) are connected by a ramp that evokes Le Corbusier’s promenade architecturale at the Villa Savoye. Along the street the villa sits atop a high artificial base featuring the pedestrian entrance and, to the side, the entrance to the garage, technical rooms and plant rooms. The successive level is a sort of loggia whose rhythm is defined by thin white columns in reinforced concrete, closed on the east side by a row of windows. The spaces at the back host the gym and games room. The solution of the artificial foundation level was necessary to set out from a well-defined ground level, compensating the steep natural slope of the site. The successful choice to differentiate the two levels in their materials and building typologies optically reduces its height to produce a more articulated and lighter overall appearance. Over the course of recent decades Villa Savarese has undergone numerous internal transformations and subdivisions, such that it now consists of diverse units inside the same envelope, whose exterior has remained largely unchanged and as it was conceived by Luigi Cosenza. Luigi Cosenza’s interest in the spontaneous architecture of the Mediterranean followed a logic of cultured re-interpretation and not a passive emulative. This signifies intelligently uniting this research, the Mediterranean as a genius loci, also with Mitteleuropean culture, aulic architecture and the work of his leading contemporaries.

The House-Refuge, a Modern Lesson

The House-Refuge, a Modern Lesson

by Eleonora Carrano

Commissioned in 1955 by the journalist Francesco Malgieri for his daughter Luciana Pignatelli d’Aragona Cortez, Villa La Saracena belongs to a “tryptic” that includes the nearby La Califfa and La Moresca villas (1967-1981). The recurring theme in these three villas in Santa Marinella is that of the house-refuge, which main objective was the creation of an autonomous space and maximum isolation from the exterior. Oriented along the north-south axis, the Villa follows the irregular and elongated form of the lot, closed between the coastal street front and the water. To the left of the main entrance is the garage, accessed via a secondary gate. The house is conceived as a long path extending toward the sea, as a fluid and continuous “crossing” that begins at the threshold of the lot. Two longitudinal axes orient the functions of the home in plan: a first axis runs from the entrance to the atrium and a second that runs from the vestibule along the galleria to the terrace extending toward the sea. The plan can be summarised as a subdivision into three functional nuclei created to be independent, though spatially connected. The first nucleus is along the street front and consists of the vestibule that leads toward the two night-time spaces; the second nucleus consists of the descending ramped galleria with flat roof and the third nucleus is composed of the dining and living room, in correspondence with which the ceiling height is doubled. The structural system is based on the use of columns. It is impossible to speak about Villa La Saracena without mentioning the restoration carried out by the architect Paolo Verdeschi, which has returned the house to its original state. The most unique aspect of this restoration is the discovery of surprising pinkish colours beneath successive layers of paint inside and outside the home. This discovery unhinged a number of certainties about Moretti’s rare concessions to colour, limited to the furnishings he had personally designed for the Villa.

Living “flexible”

Living “flexible”

by Alessandra De Cesaris

The house in Via Dezza represents the manifesto of Ponti’s idea of dwelling, in which he implemented a series of reflections and inventions matured and tested during the previous years. The house presents Ponti’s version of the free plan, that space for flexible and open living invoked from the earliest days of his career. The house was thus a large environment whose modernfold walls make it possible to join different spaces or subdivided others. The flexibility of the house in Via Dezza is first and foremost a visual flexibility, that permits the perception of the total dimension of the flat, which can be crossed by views, by light, by air. In the flat the traditional division between day-time/night-time spaces disappears and the main elevation, facing south, is defined in succession by the master bedroom, the living room, the dining room and the children’s bedrooms, all communicating with the exterior via the so-called furnished window, an entirely glazed wall that incorporates a series of furnishings. A determinant role in creating comfort is played by furnishings: self-illuminating pieces, the wall dashboard, wardrobes, the modernfold walls, lightweight solutions, all authentic inventions by this multifaceted architect who, during the course of his life, managed to create a dialogue between manufacturers and the know-how of craftsmen and to include the memory of tradition in the design of his furniture and furnishings. Even the main façade is “transformable” and adaptable to the desires of individual residents who could choose the design of the furnished window and the colour of the plaster to give the entire elevation a spontaneous dimension. What is instead surprising in this home is the absence of a roof garden and the presence of a balcony of such modest dimensions. The long cantilevered balconies, enclosed by a full-height cornice, serve in fact to define the elevation but are unable to configure a liveable outdoor space.

Evolutionary changes

Evolutionary changes

by Ruggero Lenci

These four home-studios for artists realised in 1960 in Via Mariano Fortuny in Rome look out through large windows west toward the Tiber river, while to the east they are anchored to the tufa stone face of Villa Strohl Fern. The use of “folded” shed roofs is an original solution not only on the exterior for its balanced insertion with the landscape, but also inside for the singular connotation of the living spaces. The building contains a total of four residential units: two duplexes and two simplexes, with the north and central volumes hosting the duplexes, while the south building contains one duplex on the entry floor and another on the upper floor. The ground floor is accessed via external stairs that manage the important level change. The living rooms in the duplexes were positioned on the upper floor, such that the entrance passes through the night-time spaces before rising up to the living spaces. In the first unit accessed from the left of the vestibule is an inclined wall. After passing it, we arrive in the bedroom and bathroom, surmounted by a space-glazed bridge on the two long sides. This volume, centrally positioned with respect to the other two constructions, does not project on the west side, like the end walls, but serves as a functional volumetric connection. The next unit is accessed from the second door in the vestibule and opens onto a long corridor that runs parallel to the retaining wall where it meets the spiral stair leading up to the living room, closet and bedroom with ensuite bathroom. The last two units are the simplexes accessed from the third and the fourth door. Over time a number of substantial changes were made to the volume to the north: the windows were substituted without respecting the original subdivision and design. In the volume to the south, the four original openings have been substituted by bow-windows that bring more light into the interiors. An elevator was also added to the building to the north.

Between Archetype and Model

Between Archetype and Model

by Massimo Zammerini

While very different from one another, these two houses share a particular approach to residential design, proposing a bond with an almost primordial nature. The twin vacation homes on the Bay of Arzachena in Sardinia and the Press House in Lydenburg, South Africa speak of a communion with the atmospheres determined by the landscapes in which they are located, are one storey in height and firmly rooted to the site, with a visceral attachment to the ground. The twin seaside homes feature a square plan: the four corners are marked by four autonomous stone volumes, three bedrooms and a dining room with sliding corner windows. The resulting Greek cross void of this composition is partially occluded by the kitchen, communicating with the dining area, by the oven and by a toilet accessible only from the exterior. Outdoor space is designed for communal living, with a table shaded from the sun by a trellis of wood beams supporting a filtering mat of reeds. The same attention can be found in the large home in Lydenburg, where a series of parallel walls define a very elongated plan; at the centre are the spaces of the living room from which a series of “diapason” branch out; between long walls in natural stone they contain the other internal spaces and outdoor spaces hosting “wild” gardens, a fish pond and a swimming pool. Inside these visual tunnels pointed toward the desert hills spontaneous vegetation penetrates in all directions, onto the roof. All of the other spaces feature exposed natural stone walls, wood plank floors and ceilings. The most characterising elements of this large villa are its long stone canyons inhabited by an alternation of liveable spaces and gardens that literally project from the central nucleus. The central part of the elevation facing the valley presents a series of stone buttresses that create a shaded portico. Viewed from a distance the house is perfectly integrated within the undulating landscape of hills.

The Future Coming from the Past

The Future Coming from the Past

by Raynaldo Perugini

The compositional principles underlying the so-called Casa Albero (Tree House) at Fregene, realised in collaboration with Uga de Plaisant and Raynaldo Perugini, can be synthesised in two words: experimentation and freedom. What is evident is the experimental character of so many of the solutions adopted. Similarly, there is also a manifest desire to create interiors as undifferentiated space, expandable over time and without interruption. The house is truly conceived as one of the possible aggregations of a series of modular elements in reinforced concrete and steel to be built off-site and “assembled” by bolting them together in situ. In this specific case, however, the particular building system adopted, comprised of suspended and bearing beams, columns and plates, while conceived to be industrially produced, was cast on site. It must be observed in any case that a similar choice frees up the walls of any load bearing function. An important factor that must be considered with regard to the choice to build the walls using a variety of modular elements that can be freely combined and permit the substitution of traditional furnishings, is that internal space is freed from the presence of traditionally more cumbersome furnishings such as wardrobes or bookshelves. For the glazed portions, the choice was made to accompany the modules-windows with compositions in red steel of concave and convex cubes. There exists a series of design proposals anticipating the final idea that would give form to the Casa Albero. First among them that presented in 1967 for the first InArch-Finsider competition for steel structures for residential housing which received first place. The proposal included a series of freely aggregable modules-frames to create hypotheses for housing that could potentially be extended even on different levels.

Interior Space and Domestic Rituals

Interior Space and Domestic Rituals

by Nina Artioli and Matteo Costanzo

Gae Aulenti moved in 1974, into what would become her home-office until her death in 2012. Together with her flat, she also managed to purchase a small two-storey building facing Piazza San Marco, which she transformed into her office. While the house featured very high ceilings and was reorganised by adding a second level open onto a double height space, the office facing Piazza San Marco was completely emptied and remodulated by introducing a system of offset levels. The two spaces were connected by the concealed door and crossed by a sequence of orange steel stairs and walkways. The house features a void rectangular volume, a large space projected toward the city through large vertical windows. Along the opposite wall, the second level balcony gives onto a double height space, beneath which a sequence of more intimate and functional environments host various services. The large central space defines the public dimension of the home, the dark slate paving and white walls set the backdrop to the system of tubular steel and metal grille walkways. Long white bookshelves constitute the most minimal systems of dividers and establish how space is crossed. The image is completed by a rich combination of furnishings, light fixtures, works of art and design prototypes. In the lower part of the balcony a functional wall divides the space of the large living room from the kitchen, while on the upper level it organised Gae’s private life, her bedroom, with ensuite bathroom, and a walk-in closet. The door leading to the office is positioned opposite the front door and opens onto the meeting room. The main entrance to the office is directly from Piazza San Marco. Inside orange stairs and offset floors animate a completely void envelope, bringing natural light to all levels and creating a unique space inhabited at different heights.

Living into Nature

Living into Nature

by Gianni Pettena

This small ruin was almost completely concealed by brambles. I actually discovered it by accident and fortunately managed to purchase it in 1975. Directly involved in the adventure of reconstruction, I visited often to control the works, often unconsciously “marking” the territory, like any animal. In this place I sought to create space for myself without disturbing, to slow down my rhythm, to observe, listen, learn from nature. This gradually permitted me to create a space also for myself, without destroying anything. I could speak, more than of a work of minimal architecture, of an architecture that was lived, learned, and in which context commanded and taught. Similar to a diary that uses a visual language, the house continued to be modified; it maintains the memory of its origins and I now feel it has finally taken on its more or less definitive appearance. Made of stone, glass and wood, almost entirely local, the house is a concatenation of open environments and small enclosed spaces, a co-construction by man and nature, that allows vegetation to enter: almost a utopia made reality that has acquired its own architectural value the more the environment assumed a central role. Over the course of the years contributions have been added by such friends as Ettore Sottsass, Alessandro Mendini, Nigel Coates, Lapo Binazzi, Ugo Marano who have contributed to making this place so particular. Ettore Sottsass gifted to me and the house his last work, a wall and a fireplace; the wall beside it is designed by Alessandro Mendini with a mosaic at its centre; two tables, one inside and one outside, are by Ugo Marano, who enriched these objects-furnishings with mosaics and ceramics. Andrea Branzi designed a weather vane on the roof, Lapo Binazzi a clothes hanger Nigel Coates a table and Marco Pace a bathroom. More than a project curated by me, I wished to add an additional “flavour” to the house through interventions by my friends, traveling companions that would demonstrate their understanding of the significance of dwelling in this place.

EXPERIMENTS ON THE CONTEMPORARY HOME. HYBRID INTERIORS. SPACES OF TRANSITION – Pg. 92

Luca Galofaro

ARGOMENTI

– Abitare in Cina. La politica della città e della casa – Pg. 106

– Il valore del vuoto nella casa mediorientale – Pg. 115

– Carlo Aymonino. Progetto, città e politica – Pg. 118

NOTIZIE – Pg. 122

LIBRI – Pg. 126

Questo post è disponibile anche in: Italian